One way commercial maritime technology helps navies

Promas, the propeller-rudder system that has been raising efficiency and reducing fuel use by commercial vessels for years, offers big benefits to navy users as well. It is one of many examples of commercial technology finding application with modern naval demands

Naval vessels can have an enormous range of operational profiles – even for just one platform. A sub-hunting frigate might want to be dead-quiet at 15 knots while patrolling, but then burst to 25 or 30 knots in a sprint to target.

A carrier support vessel, be it frigate or resupply ship, may need to keep pace with a US nuclear powered aircraft carrier that travels at high speed for long periods.

Navies that operate around the world need to ensure that their vessels can deploy longer, and they can do that by consuming less fuel.

But the classic navy underwater propulsion arrangement featuring twin propellers and off-centre rudders may be hindering the capabilities expected of modern naval vessels.

Propeller and rudder solutions developed by Kongsberg Maritime for the commercial marine world provide a ready-made answer to the need for greater range.

Kongsberg Maritime’s Hydrodynamic Research Centre (HRC) in Sweden recently confirmed that the Promas propeller and rudder system can be used by navies to achieve a significant gain in efficiency, and therefore a cut in fuel consumption – as much as 6% in some cases – as well as increased manoeuvrability.

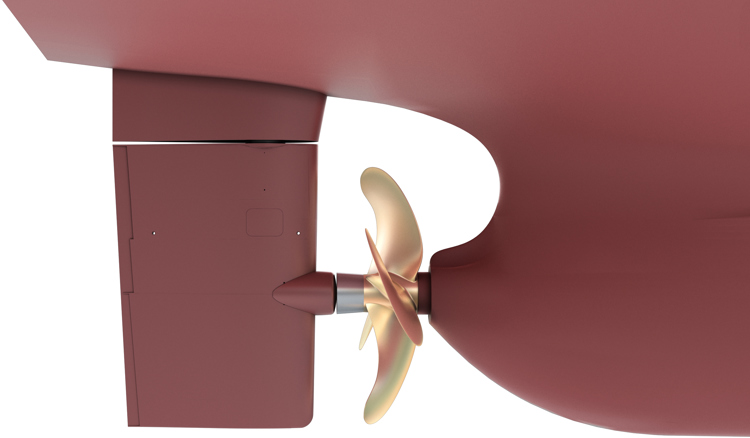

Promas essentially combines propeller, shaft brackets, and rudder into one unit, allowing the hydrodynamic design to be fine-tuned to achieve greater benefit. Each element works with the others to ensure no propulsion power is lost.

The HRC test compared a Promas bulb-rudder system with the conventional off-centre rudder system in an open shaft configuration with V-bracket and a high shaft inclination angle typical of a modern navy vessel. The Promas system set up used the same propeller type and shaft angle.

Engineers and analysts at the HRC built scale models of both arrangements and then tested them in the HRC’s special-purpose cavitation tunnels, which allow analysts to precisely monitor and measure the effects at various speeds. In this case, the HRC tested speeds of 15, 20, and 25 knots and assessed the results.

The test compared propulsive efficiency, rudder forces, cavitation inception speed, cavitation, pressure pulses and noise levels between Promas and the conventional navy propulsion set up.

At 25 knots, the cavitation patterns on the propeller blade were similar for both the conventional system and the Promas set-up. But the efficiency gains were notable, with a 6.3% gain at 15 knots, a 5.9% gain at 20 knots, and a 5% gain at 25 knots.

We’re continuing our research to consider how Promas could enhance the operational capability of combatants which operate at up to 30 knots

Underwater noise and cavitation inception speed were the same for both systems. However, the Promas system also shows improved manoeuvrability and lower pressure pulses that would vibrate through the ship’s structure.

Patrik Kron, Kongsberg Maritime’s Chief of Naval Systems, says that development of a Promas system suited for high-speed ferries may wind up yielding advantages for navies needing vessels to operate at higher speeds.

“We know there is a large market for grey (combatant) and light grey (non-combatant) navy ships operating up to 25 knots, so our initial research has focused on that speed range,” says Kron. “But we’re continuing our research to consider how Promas could enhance the operational capability of combatants which operate at up to 30 knots.”

He adds that multipurpose frigates, often the largest vessels that navies operate, may wind up in a carrier group, as found in the US, UK, France, where speed is an issue. “If you must follow a US nuclear-powered carrier running at 30-knots, then that adds of requirements on the machinery and fuel capacity of a supporting ship,” says Kron.

Propeller and shaftline systems by Kongsberg Maritime

Promas technology has been available to the commercial shipping industry for 15 years, with over 200 applications worldwide. The system can be part of a vessel refit, which can introduce significant gains without significant costs.

The pairing of results from CFD testing with in-water scale model testing in cavitation tunnels also shows the value of Kongsberg’s Hydrodynamic Research Centre, which has decades of experience working with naval requirements.