A propeller on a pedestal in the middle of the roundabout tells us that we will soon arrive at KONGSBERG Hydrodynamic Research Centre, just outside the Swedish town of Kristinehamn. Propellers have been produced here, on the shores of Lake Vänern, since 1930.

It all started with the production of impellers for water turbines when Sweden began to utilise hydro power in the late 19th century. From there, the production moved over to ship propellers. The team in Kristinehamn can look back on more than 80 years of development and production of propellers for ships all over the world.

We start our visit at the research centre devoted to the study of hydrodynamics. This is the study of the movement of liquids and gases at the macro level, for instance how water behaves when it comes into contact with a rotating propeller. At the centre, we are met by Mattias Neumann, Senior Vice President Propellers, and Göran Grunditz, Head of KONGSBERG Hydrodynamic Research Centre and Key Technology Owner for Hydrodynamics.

Göran puts on a video that illustrates the core of what they do here at the centre. In the video, we see a propeller spinning around in the water in slow motion. With each rotation, bubbles of water vapour appear on the edges of the propeller blades. This phenomenon is called cavitation, and it presents a constant challenge for those working with hydrodynamics.

“Cavitation creates noise in the water and vibrations in the ship and can cause the propellers to erode,” says Göran Grunditz, who has worked in propeller design for 20 years.

Mattias Neumann, Senior Vice President Propellers, and Göran Grunditz, Head of KONGSBERG Hydrodynamic Research Centre and Key Technology Owner for Hydrodynamics.

The world’s best propeller

Today, Kristinehamn has an impressive track record, with customers in around 120 countries across the globe. They supply propellers for marine vessels that have specific demands for low levels of noise and vibration, such as cruise ships that want quiet propellers in order to protect marine life while at the same time reducing fuel consumption. In recent years, half of new sales have gone to marine vessels, the rest to the merchant marine and offshore.

Independent testing has shown again and again that the propellers from Kristinehamn are the best on the market. Many customers choose to conduct what they call a race, where different propeller designs are tested against one another.

“When we’re in a situation where the customer wants to test the propeller, it is very seldom that we don’t emerge victorious from the competition. It is precisely this hydrodynamic ability that allows us to develop the quietest, most fuel-efficient propellers and meet other specific demands the customers may have. We are the only company on the market with this ability,” says Mattias Neumann, Senior Vice President Propellers at Kongsberg Maritime Sweden AB.

In addition to propeller design, Kristinehamn supplies what they call pods. These are propulsion systems that use an electric motor connected directly to the propeller shaft. The entire pod hangs beneath the vessel and derives power from generators or batteries on board the ship. The pod can be turned 360 degrees for increased manoeuvrability. The pod is available as either a pusher propeller or as a propeller that pulls itself forwards through the water, like the propeller on a plane does in the air.

“ELegance, as we’ve named our latest pod, is truly a product for the future. The trend in ship propulsion is moving towards more electric designs, especially in the cruise segment, where the environmental regulations have become stricter,” says Mattias Neumann.

Kristinehamn is also developing water jets, wherein the water is sucked into the hull and pumped out aft. The branch cooperates closely with Kongsberg Maritime’s branches in Finland, as well as in western Norway.

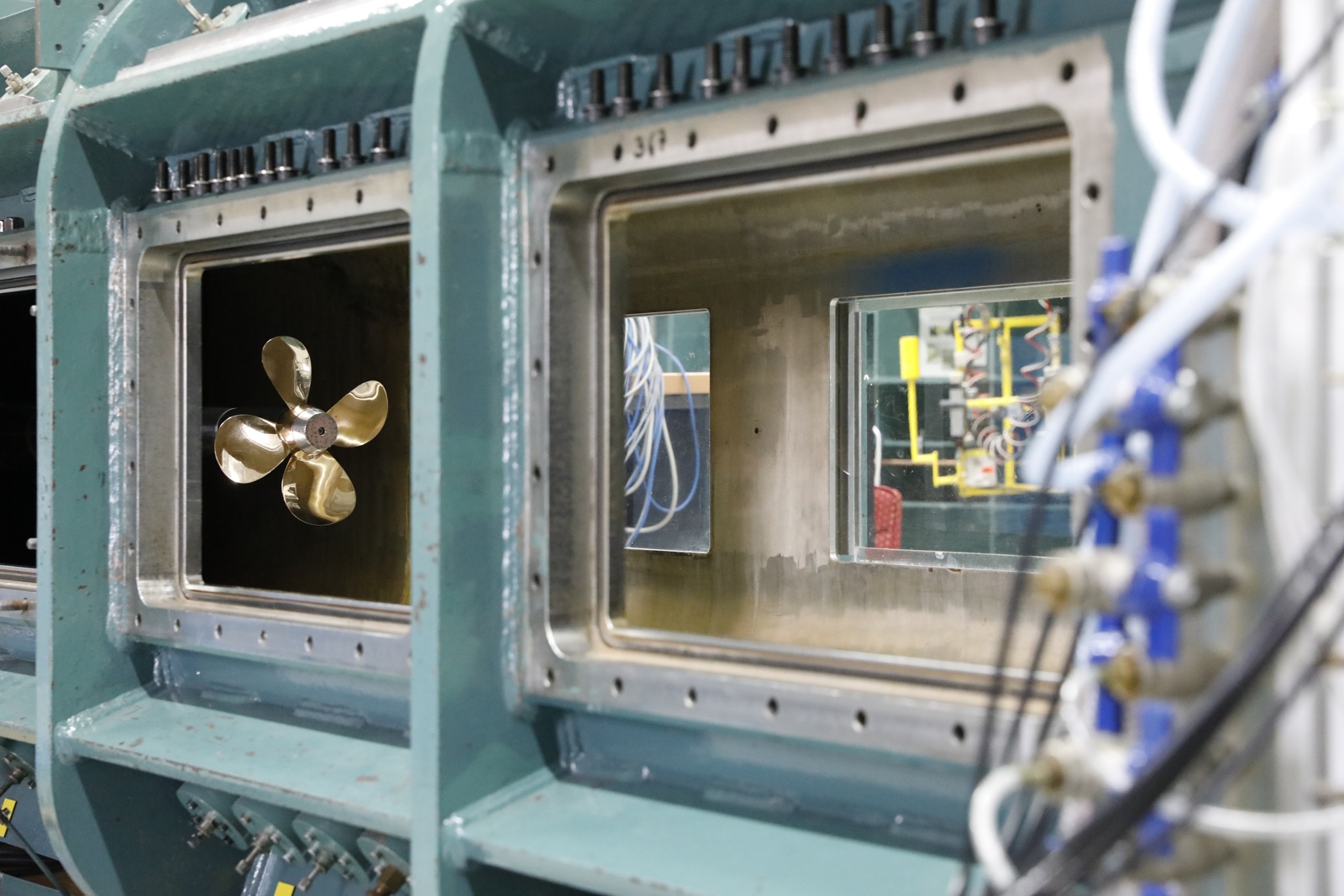

The large cavitation tunnel holds 400 cubic metres of water, which are pumped towards a scale model of the propeller design being tested.

Trial and error in a water tunnel

The movement of water is complex and has challenged physicists and mathematicians for centuries. It is precisely this scientific approach that elevates the propulsion systems from Kongsberg Maritime in Kristinehamn above the competition.

Mattias Neumann and Göran Grunditz lead the way into the testing facility, where metre-thick pipes run from the floor to the ceiling of the four-storey building. The facility can be described as a wind tunnel, where there’s water flowing through the tunnel instead of wind. The large cavitation tunnel holds 400 cubic metres of water, which are pumped towards a scale model of the propeller design being tested.

“A ship propeller isn’t a stock item; a new one gets designed for every single vessel. The design is adapted to the size of the ship, its speed, noise and vibration requirements and whether it needs to be able to go through ice,” explains Göran Grunditz.

Through the glass of the water tunnel, Göran and his colleagues can study what happens when the water meets the propeller at various speeds. Due to the complexity, it is not yet possible to sufficiently account for all factors through simulation. It is often faster to create a model rather than waiting for the computer calculations.

Along one wall is a row of cabinets with numbered models of propellers. The collection goes back to the 1930s and includes around 1,600 propellers with varying blade angles and shapes. And that’s not including the propellers for military vessels. The designs for those are subject to strict security requirements.

“The propeller on a marine vessel is a closely-guarded military secret,” Göran tells us.

On the shores of Lake Vänern

We thank our hosts for showing us around the KONGSBERG Hydrodynamic Research Centre and continue on to the head office, located 10 minutes away on the shores of Sweden’s largest lake, Vänern. There are currently around 260 employees working at Kongsberg Maritime’s Kristinehamn location. In 2016, the actual machining of the propellers was separated from the business. Now Kongsberg Maritime is in charge of assembly, which takes place in the workshop hall that we will soon be visiting.

First, we’ll be meeting two of the people who work to supply customers with the world’s best propeller and propulsion systems. Lars-Johan Mårgård leads the delivery team in Kristinehamn, which consists of 12 project managers. He describes a hectic but rewarding working life in Kristinehamn.

“You’re part of the whole process, from the order to the customer receiving the solution we developed for propelling their vessel. Closeness to the customer, closeness to technology, involvement in the whole process from sale to final installation – these are things I value,” says Mårgård.

Maria Bergsman works in the same department, and is currently in the middle of several delivery projects.

“One of the projects is for Damen Shipyards in the Netherlands, which is building a hybrid cruise ship for SeaDream Yacht Club,” says Bergsman.

For this project, Kongsberg Maritime is supplying ELegance pods from Kristinehamn as part of a larger package that also includes Bergen engines, stabilisation, and bridge and automation systems, accompanied by a comprehensive electrical, navigation and hybrid technology package.

“I feel that the team here in Kristinehamn is truly passionate about all the exciting technology we help to supply and ensuring the customer is satisfied,” says Lars Johan Mårgård.

Along one wall is a row of cabinets with numbered models of propellers. The collection goes back to the 1930s and includes around 1,600 propellers with varying blade angles and shapes.

Profitable after-market, challenges in new sales

The most profitable part of the business in Kristinehamn is currently the after-market. Propellers from Kristinehamn can be found on vessels all over the world. Using GPS and AIS data, Kongsberg Maritime can track where vessels with their propulsion systems are located at any given time and what speed they are maintaining.

If, for example, they discover that a vessel’s average speed deviates from that for which the propeller was designed, a change of propeller could spare the shipping company major fuel costs and emissions over time, says Mattias Skrinning, head of Global Customer Support.

Knowledge regarding what is delivered and where is the most important asset Mattias Skrinning and his colleagues have.

“If a vessel is designed for 25 knots but chooses to go at 17 knots, it will take about 18 months to make up the cost of switching to a propeller designed for that speed. So, we are always proactive on our customers’ behalf and suggest any maintenance they should carry out and improvements they should make,” says Skrinning.

“What does the market for new sales look like going forward?”

“There is greater unrest in the world and many countries are gearing up. So, we’re seeing an increased volume of marine vessels and upgrading of naval fleets. We are very confident that our new ELegance pod will do well in many segments such as Ro-Pax, cruise and large yachts. All in all, there are many markets that look okay for the time being, where we expect increasing volume going forward,” explains Mattias Neumann.

A hydraulic system makes it possible to change the angle of the propeller blades even after the propeller has been installed on the vessel.

Megapropellers

Our visit to Kongsberg Maritime’s facilities in Kristinehamn concludes in the hall where the propellers and shafts are assembled before being sent out to shipyards around the world. Here we are met by Thomas Wernholm, who enthusiastically shows us around and explains how the logistics work.

Kongsberg Maritime has delivered propellers with diameters as great as 9.4 metres. A hydraulic system makes it possible to change the angle of the propeller blades even after the propeller has been installed on the vessel. In one corner of the hall, a group of employees has connected hydraulic hoses to a propeller hub. The mechanics are tested here before the product goes out to the customer. In another part of the hall, propellers and shafts are carefully packaged and approved for dispatch. Stacks of wooden planks are ready for building boxes around the propellers that are being shipped out.

“No two propellers are exactly the same, so here we build the packaging from scratch to ensure that the products are stable during transport,” explains Thomas Wernholm.

Following the acquisition of Rolls-Royce Commercial Marine earlier this year, “from bridge to propeller” has been a key motto for Kongsberg Maritime. Our visit to Kristinehamn demonstrates some of the scope of the activities relating to ship propulsion that have now become part of Kongsberg Maritime.

The branch in Kristinehamn also cooperates closely with Kongsberg Maritime’s branches in Finland, where the actual production of thrusters, pods and water jets takes place. The propellers produced in Ulsteinvik, Norway, also benefit from the expertise in hydrodynamics here in Sweden.

Lars-Johan Mårgård leads the delivery team in Kristinehamn, which consists of 12 project managers. Maria Bergsman is currently in the middle of several delivery projects.

Knowledge is capital

As we discussed in the introduction, its hydrodynamic abilities are the key factor that makes Kongsberg Maritime in Kristinehamn the best in the world when it comes to propeller design. In the development of new propellers and pods, the engineers have also looked at how the flow of water from the propeller towards the rudder can be optimised. According to Neumann, there is even more efficiency to be gained from optimising the interaction between hull, propeller and rudder.

“We would really like to be involved in the early stages of the projects and work with the people who design the vessels. We have developed a product we call Promas, where the propeller and the rudder are integrated into one system for optimal hydrodynamic efficiency. The next step is to influence the form of the entire hull in order to provide the customer with the best solution. And that knowledge is here in Kristinehamn.

The fact that the capital is found in the employees’ knowledge is a point Matthias Neumann wishes to drive home.

“The knowledge of the workers here in Kristinehamn is what creates all of this. It’s been built up over many years. We are building upon the hydrodynamic and mechanical skills of our engineering team.

“You are now a part of Kongsberg Maritime. What opportunities do you think that will open up in future?”

“We are really looking forward to becoming an integrated part of Kongsberg Maritime. We have already begun to meet people from different parts of the system, which opens up the possibility of exciting collaborative projects. We think it is very exciting to see the knowledge KONGSBERG possesses within sensors and robotics, and as part of Kongsberg Maritime’s Integrated Solutions we see increased opportunities to deliver complete systems from bridge to propeller going forward,” concludes Mattias Neumann.